Can ‘the people’ solve climate change? France decided to find out.

Nov 15, 2021

At first, Sylvain Burquier thought it was a joke.

It was August 2019, and Burquier and his two children were at their home in Paris’s Ninth Arrondissement, off the right bank of the River Seine, when his phone rang. It was a representative of the French government calling to ask if the then- 45-year-old marketing manager would participate in a political experiment. President Emmanuel Macron wanted to slash the country’s carbon emissions over the next decade, and he was enlisting a group of randomly selected citizens to help him.

It was a bizarre request — but one that, given recent history, made some sense. The French president’s previous attempts to address climate change had run aground, tanking his popularity and throwing the country into turmoil. Just a year and a half into his first term, in November 2018, hundreds of thousands of protesters clad in yellow reflecting vests (known in France as the gilets jaunes) took to the streets to protest Macron’s fuel tax increase, which would have lifted the levies on gasoline and diesel by up to 25 cents per gallon in an effort to speed the country’s shift away from fossil fuels. The gilets jaunes burned cars and smashed windows, covering walls and statues across Paris with anti-Macron graffiti. “We’ve cut off heads for less than this,” read one scrawl on the Arc de Triomphe.

Macron eventually suspended the fuel tax, and a few months later, he announced a new strategy: The government would spend 5.4 million euros ($6.3 million) to create a 150-person, randomly selected “citizens’ convention on climate.” The group would advise the French parliament, and the president himself, on how to cut carbon pollution.

It was not the first time that randomly selected citizens had been asked to advise — or even stand in for — politicians on the most contentious issues of the day. Over the past few decades, assemblies focused on everything from gay marriage to nuclear power have taken place in Asia, Europe, and North America. In 2017, a citizens’ assembly in Ireland drafted new recommendations on abortion, which lead to its legalization in the largely Catholic country a year later. In Texas, several “deliberative polls” (a poll, town meeting, and lecture wrapped into one) of utility customers between 1996 and 1998 helped turn the fossil fuel-filled state toward wind power. The world, according to a report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, is witnessing a “deliberative wave” as governments eschew traditional modes of democracy for new, experimental forms.

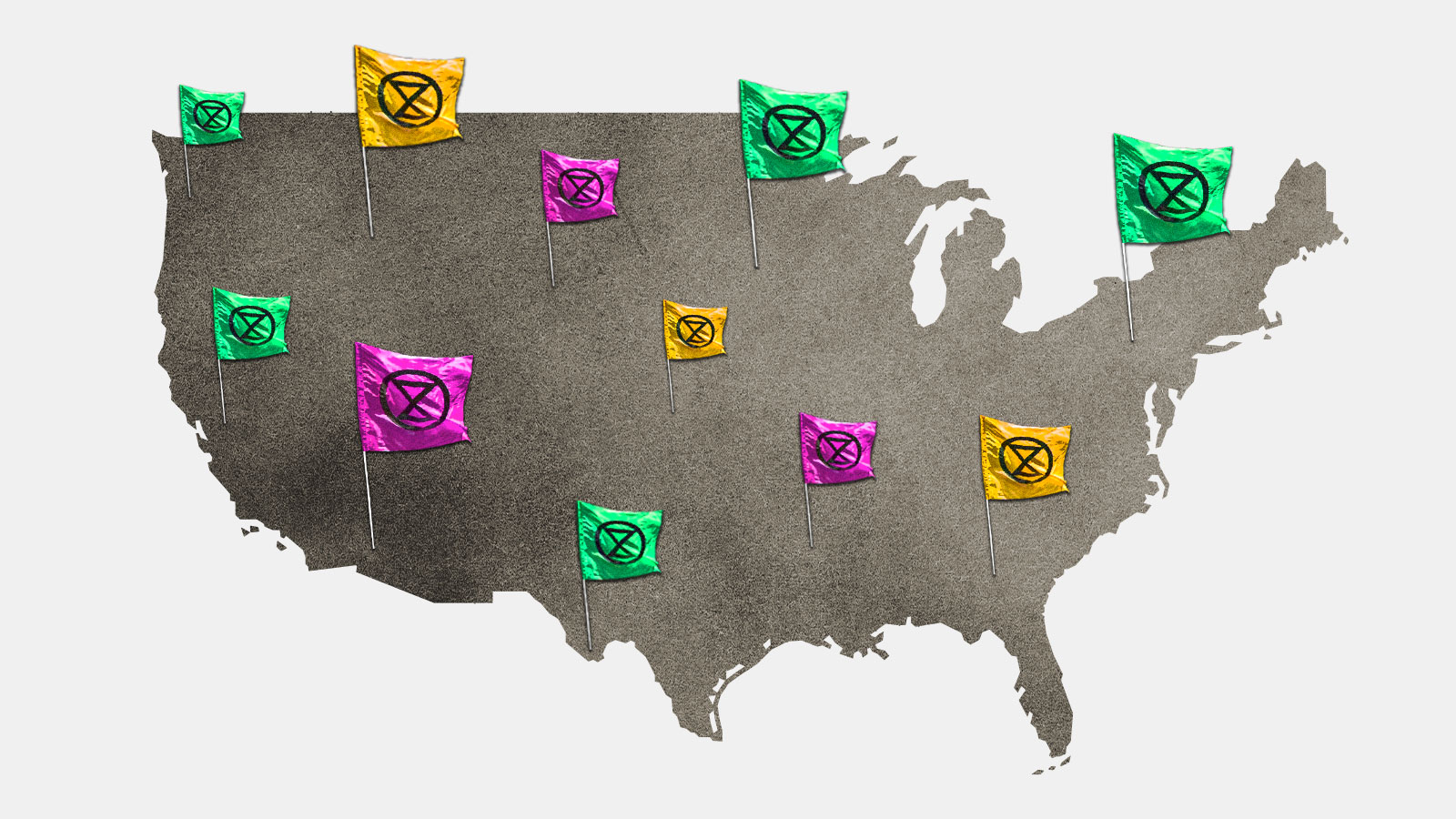

Proponents say that citizens’ assemblies can dissolve partisan boundaries, return power to the people, and — on the problem of climate change — break through a political gridlock that endangers the entire planet. Over the past several years, dozens of assemblies focused on climate change have taken place in Europe and the U.S. One group even attempted to create a 100-person “global assembly” on climate change in the run-up to this month’s international climate talks in Glasgow, Scotland.

Whether such groups can succeed and what, in fact, should count as a “success” remain open questions. Unlike legalizing abortion or gay marriage, converting a country’s entire energy system to low-carbon sources is deeply technical — perhaps too much so for a hundred randomly selected people to fully grasp, let alone solve, over the course of a few months. Citizens’ assemblies also vary widely in their structure and the support they garner from government officials. Should an assembly be a kind of glorified focus group, a venue for citizens to share their views? Or can it actually help generate and pass new legislation?

On the phone, Burquier answered questions about his age, gender, educational background, and profession. Then, he waited. The government had called or texted approximately 255,000 people, and only a small fraction would be selected through a method called “sortition,” which would attempt to recreate the demographics of the country in miniature. (Most demographics, anyway: France doesn’t recognize race or religion in its statistics.)

Two months later, Burquier got another call: He was in. Roughly once a month for the next nine months, he — along with 149 other French voters — would report to an ornate government building in the center of Paris, less than half a mile from the Eiffel Tower. They would meet with legislators, scientists, experts, and Macron himself, crafting recommendations on how the government should tackle climate change.

They were also equipped with a pledge from Macron: that he would submit their final proposals to the French Parliament, put them up for a public referendum, or sign them directly into law sans filtre — “without filter.”

It was a promise that he would find difficult to keep.

It’s often said that democracy is in decline, crumpling under the weight of staggering inequality, the lightning speed with which online misinformation spreads, and a rising populism that rewards politicians with an authoritarian bent.

According to the Pew Research Center, 65 percent of Americans believe that their political system needs either “major changes” or “to be completely reformed.” Sixty-eight percent of French adults feel similarly about their system, as do 47 percent of those in the U.K. about theirs. Some have argued that countries are entering an era of “post-democracy,” in which the standard trappings of democracy continue (regular elections, a free press, separation of powers) but elected representatives rarely give voters what they want. In 2014, political scientists at Princeton University and Northwestern University analyzed over 20 years’ worth of U.S. policy data and found no correlation between the preferences of the majority and actual political outcomes. Some 81 percent of Americans support wider background checks for gun purchases, for example, but Congress has shown little interest in passing stricter gun laws. “When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites or with organized interests, they generally lose,” the authors wrote.

Climate change is no exception. Although citizens of many countries view global warming as a serious threat, international climate summits — including COP26 in Glasgow — have seen far more talk than action. Since 1992, when representatives from more than 150 countries gathered in Rio de Janeiro and pledged to limit the buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, global CO2 emissions have actually risen by more than 60 percent. Some individual countries have succeeded in reducing the greenhouse gases they spew into the sky (the United Kingdom, for instance, has managed to cut emissions by 38 percent since 1990, largely thanks to a phaseout of coal), but most are lagging far behind. Attempts to levy higher taxes on pollution in France and Canada have run into popular protest and, despite current efforts in Congress, the U.S. hasn’t passed significant climate legislation since 2009.

Against this backdrop, citizens’ assemblies can seem like a remedy — or potentially a last resort. Gather 100 to 150 average voters in a room, the thinking goes, and they might be able to cut through polarizing divides and come up with new, innovative policies.

Hélène Landemore, a professor of political science at Yale University and the author of Open Democracy, told me that, in theory, citizens’ assemblies can be more representative than traditional democracies — and ultimately, more fair. Most governments give power to elected officials who often already have power in the form of money, connections, or public recognition. Citizens’ assemblies hand power directly to the people (or at least, a randomly selected subset of them). “It’s not that elected officials are bad individually,” Landemore said. “But as a group, they tend to lack diversity, and they tend to be blind to certain problems.”

There’s evidence that putting people with opposing opinions in the same room can help root out polarization. In 2019, two Stanford professors gathered 523 registered U.S. voters in the small town of Grapevine, Texas, just outside of Dallas. They were part of a project called “America in One Room” — a four-day “deliberative poll” on issues ranging from immigration to whether the country should start providing each citizen $1,000 per month in universal basic income. At the beginning of the experiment, Republicans and Democrats were torn on essential questions around health care, taxes, and the environment. By the end of the long weekend, however, the poles had shifted toward the middle. Among Democrats, support for a $15 minimum wage dropped from 83 percent to 59 percent, while Republicans’ support for visas for low-skilled workers jumped from 31 percent to 66 percent. (Discussions about the environment and climate change produced smaller shifts in opinion.)

But changing opinions is not the same thing as changing policy — and there, citizens’ assemblies have had a more rocky history. Recommendations are rarely implemented directly by governments; at best, they are often submitted to a public referendum. In Ireland, a constitutional convention in 2012 and the citizens’ assembly in 2017 recommended legalizing gay marriage and overturning a constitutional ban on abortion, both of which later passed in country-wide referenda. A 160-person assembly in British Columbia in 2004, on the other hand, recommended changes to the province’s voting system that were later narrowly rejected by the population at large.

David Farrell, a professor of political science at the University of Dublin who helped advise the Irish government on its assemblies, says that success can come down to the topics at hand. It’s best, he said, if they provoke some kind of “underlying emotion” that can capture public attention, as hot-button issues like gay marriage, abortion, and climate change might.

But there isn’t consensus on what, in an ideal world, assemblies should strive to accomplish. Farrell argues that assemblies can play a somewhat advisory role, both by demonstrating that there is public support for controversial policies — as in Ireland’s abortion case — and by providing politicians with cover against future backlash. (That’s something Macron might have found useful after the Yellow Vests protests.) “These processes help guide politicians,” Farrell said. “That doesn’t mean you have to agree with them, but you have to engage with them.”

Others, including Landemore, have suggested a more sweeping role for assemblies — as a third house of a legislature, or as a replacement for the current form of representative democracy altogether. She pointed to a group of citizens, selected by lottery, who played a vital role in the first democracy. “We have a historic precedent,” she said. “The Council of 500 in ancient Greece.”

The first weekend that the 150 members of the French convention met in October 2019, Burquier experienced what he and other members came to call “la claque,” or “the shock.” The members had gathered in a tiered, wood-paneled amphitheater of the French Economic, Social, and Environmental Council building, the Paris home of France’s third (and purely advisory) house of parliament. It was designed to look and feel grandiose: Microphones lined the semicircular room, and cameramen and journalists hovered in the background. The citizens, sitting in plush red chairs with briefing papers and notebooks spread out before them, looked for all the world like lawmakers.

The convention proceeded in two parts. For the first several sessions, the assembled citizens learned about climate change and proposed solutions; in the final months, they deliberated and prepared their recommendations. In the amphitheater of the council building, or in its more airy, columned atrium, participants listened to scientists, policy experts, and diplomats explain the dangers of greenhouse gases and how they touched every component of modern life. They were then split into five groups, each focused on a subject — consumption, travel, housing, production and work, and food — and tasked with coming up with recommendations that would help France cut its carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2030, compared to 1990 levels.

As scientists and other experts began to describe the crisis of climate change, Burquier said the assembly was struck by the enormity of the problem — and the enormity of what they were being asked to do. “They said, ‘Now it’s your job to propose solutions,’” he said. “It felt like a very big hole that we had to fill.” France, he noted, is a country of 67 million people; each member of the convention was effectively being asked to represent 450,000 other citizens.

The assembly was expected to be confined to eight weekends, but the deliberations soon took over participants’ lives. On Friday and Saturday evenings, they would congregate at a nearby hotel — where those from outside Paris stayed during the convention — or at restaurants, drinking beers and discussing what they had learned away from the prying eyes of journalists and researchers.

Amandine Roggeman, a 27-year-old Parisian who works in fundraising at the Palace of Versailles, told me that she and many other convention members began to do their own reading during the week, stealing time after work. “The normal weekend sessions,” she said, “were just the tip of the iceberg.” After COVID-19 forced a meeting online, they started congregating over Zoom during the week, sometimes from 6 to 9 p.m. (For their nine months of effort, each participant was paid 1,462 euros, or $1,695.)

Despite the contentiousness of the issues, members of the assembly insist that disagreements were minimal. Faced with the stark 2030 goal, Roggeman said, “You feel like you don’t have time to argue.” Her group, which focused on consumption, sometimes sparred over the importance of buying local (low-carbon, but too expensive for many poor, rural members of the convention). Once COVID-19 struck, they haggled over whether the convention would go fully remote or remain in-person. Most of the issues were resolved through careful conversation, thanks to trained political mediators who were hired for the occasion to help ensure that everyone received roughly equal time to speak and that discussions didn’t devolve into infighting. “Those people were essential,” Roggeman told me. “They were the ones putting oil in the machine.”

The real conflicts came between the members of the assembly and the organizers themselves. Every hour of each weekend had been carefully planned in advance, and as the months wore on, the assembly began to get restless, frustrated that — despite their role as selected representatives of the French people — they had little control over the convention’s operations. They feuded with the organizers over voting procedures, the selection of speakers, and the schedule. Once, when an expert came to talk about the benefits of a carbon tax, they grew angry, sensing that they were being led toward the political “third rail” that had sparked the gilets jaunes protests in the first place.

But the members gradually found that the organizers were essential to the smooth running of the convention. One day, during a discussion about a trade agreement between the European Union and Canada, they insisted on being left alone for two hours to debate — without any mediators or organizers present. The meeting devolved into a shouting match, and one by one all of the members walked out. After that blowup, Landemore, who spent months observing the assembly, said the group was more amenable to the organizers’ suggestions. “It’s not that they’re children in need of control,” she said. “But they are a large number of people — they need structure.”

In June 2020, after months of work, the convention finally released its list of 149 proposals. Burquier was jubilant. Their ideas were comprehensive, covering all aspects of French life, and some were radical. They recommended banning the construction of new airports, taxing corporate dividends to pay for green programs, and revising the constitution to make damaging the environment a crime. Others seemed commonsense: Members supported mandatory recycling and removing oil and coal heating systems from homes.

The members were eager to present their proposals to Macron. The president had visited the convention multiple times to answer questions and encourage the group to take its job seriously.

Philippe Wojazer / AFP via Getty Images

But just days after the convention released its recommendations, the tacit agreement Macron had made with the convention — that he would submit the recommendations to parliament or to a nationwide referendum “without filter” — began to break down. In a speech to convention members on the lawn of the Élysée Palace, the French president’s official residence, Macron announced that he was rejecting three of the 149 proposals, including a tax on corporate dividends to fund green programs and a nationwide speed limit of 68 miles per hour. A national speed limit, Macron warned, could prove too controversial; a tax on dividends might discourage investors. He called the canceled proposals his “three jokers.”

That was just the beginning. Over the next few months, members of the convention watched in frustration as government ministers discarded or watered down many of their remaining recommendations. The ban on new airports was thrown out, as was a plan to incorporate the fight against climate change into the country’s constitution. Members of the assembly were sometimes asked with little notice and no preparation to appear before government committees or lobbyists to defend their proposals.

Landemore, the Yale professor, saw the group’s frustration firsthand. “Those proposals were their baby,” she said. “They felt like they were being cheated.”

Members began pushing back. Some gave interviews to French television. Burquier, who had never appeared on TV or radio before, soon became comfortable making public appearances. Last October, the members wrote an open letter to Macron, imploring him to follow through on his original promises. Cyril Dion, a French documentary filmmaker and one of the convention’s “guarantors,” started a petition online to “save the citizens’ convention on climate,” which ultimately garnered over 500,000 signatures. “We are asking today that the President of the Republic keep his word,” Dion wrote.

By December, Macron had had enough. In an interview with the French media site Brut, he lashed out. “I have 150 citizens. I respect them,” he snapped. “But you can’t say that just because 150 citizens wrote something, it’s the Bible or the Quran.”

“We were too much pressure for the government,” Burquier told me. It was a Frankenstein moment, he explained: Macron had created a monster, and then lost control.

While the 150 members of the French convention were meeting in the Parisian council building, other assemblies continued popping up all over the globe. More than a dozen climate assemblies have taken place in U.K. cities over the last few years, sparked in part by the U.K.-based activist group Extinction Rebellion. In January 2020, six committees of Parliament helped form a 108-member climate assembly in the United Kingdom, with a goal of helping the country reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. And in Washington state, an 80-person assembly convened over Zoom at the start of the year to recommend climate policies to the state legislature.

Almost all of these assemblies have shown that randomly selected citizens can agree — at least in a managed, mediated environment — on major policy changes. The U.K. assembly, for example, proposed levying a tax on frequent flyers and reducing the country’s meat consumption by up to 40 percent. The Washington Climate Assembly endorsed building electric vehicle chargers and investing in carbon capture technology.

But the results have been mixed in terms of assemblies attracting attention, let alone getting policies passed. The U.K. assembly was designed more like a focus group, a venue to gauge public opinion; it wasn’t expected to formulate new legislation or new policy. (It also had one-tenth of the funding given to the French assembly.) Its final 50-plus recommendations were covered by the media and discussed in Parliament when they were released last year, but Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government offered no concrete promise to follow through.

In Washington state, Barry Scovel, a 67-year-old member of the climate assembly, told me that the group had a “Meet & Greet” with state lawmakers over Zoom in March, but within 10 to 15 minutes the legislators began dropping off, with some giving apologies. They were in the middle of a legislative session and didn’t have time to listen to all of the assembly’s suggestions.

Against that backdrop, the French assembly’s tussles with Macron start to look like features rather than bugs. “The French model is far from perfect,” said Rich Wilson, a deliberative democracy expert and director of the U.K.-based social impact lab Osca. But, he added, the discussion started by the 150 citizens was mirrored around the country, and many of the group’s recommendations — a nationwide 68-mile-per-hour speed limit, for example, or a push for vegetarian meals — were debated and discussed by the wider French public. That national discussion, Wilson says, is the “critical success criteria” that can spark political change.

Landemore agrees. Although she found Macron’s “without filter” promise a bit foolish — “of course there would have to be some kind of filter,” she told me — she thought the president’s vow, and the resulting conflict, brought attention to the convention. Some 70 percent of French citizens had heard of the convention by the time it had wrapped up its work in June 2020, according to polling commissioned by the Climate Action Network; 64 percent considered its work “useful.”

Proponents of assemblies argue that there’s no reason the model can’t succeed elsewhere, including in the United States. While the U.S. is more polarized than France on climate change — only 70 percent of Americans polled think that the planet is warming, compared to 92 percent of French respondents — similar projects have worked in the U.S. in the past. In the 1990s, those meetings in Texas with utility customers turned skeptics of wind power into supporters. Before the eight sessions, only 52 percent of participants were willing to pay more on their utility bills to support renewable energy. Afterward, the number jumped to 84 percent.

And despite deep differences between political parties, a majority of Americans of all stripes want action to rein in greenhouse gases. According to a Pew Research poll conducted earlier this year, roughly 8 out of 10 Americans surveyed support further development of wind and solar energy, and two-thirds think the government should do more to address climate change. Another 80 percent of Americans, meanwhile, approve of the idea of creating citizens’ assemblies.

“Americans always think they’re so different from the rest of the world,” Landemore, who is French, told me. “But we’re all just human beings.”

One concern is that, even with support from governments, a group of 150 citizens might not come up with solutions that actually work to combat climate change. Lorraine Whitmarsh, an environmental psychologist at the University of Bath who served as one of the experts for the U.K. assembly, said that the British participants loved “anything informational or educational,” like programs to label the carbon footprint of products or push citizens to eat less beef and pork. Such initiatives are popular — “Who wouldn’t agree with having some labels?” Whitmarsh asked, ruefully — but such piecemeal policies would fall far short of what’s needed to dramatically decrease carbon emissions.

There’s also a concern that assemblies could be too easily influenced, with organizers shaping their recommendations. According to Landemore, the team of experts who designed the French convention had decided that nuclear power shouldn’t be discussed, despite the fact that it provides around 70 percent of the nation’s electricity. Wilson, the deliberative democracy expert, told me that how information about climate change is conveyed to assemblies — as a problem to be managed or as a stark, existential emergency — could affect whether the assemblies propose huge, society-altering changes such as a ban on coal power, or just policy tweaks, like extra recycling.

In July, both houses of the French Parliament passed the country’s new climate law. It was inspired by the work of the convention, but only loosely. According to an analysis by FranceInfo, only 10 of the convention’s proposals made it into the law in truly “unfiltered” versions; 36 others were included, but in weakened form.

“Some of the measures were there, but not of the intensity we wanted,” Roggeman said. “It was always like, ‘Oh, we’re postponing the dates,’ or ‘Oh yes, we’ll forbid cars of a certain weight’ — but not the weight we asked for.”

Christophe Archambault / AFP via Getty Images

As the law was being drafted, members of the assembly were often angry, frustrated by what they saw as the failure of Macron to follow through on his promises. The convention met again in February, this time to give the government a score (out of 10) on how well it had implemented their proposals thus far: The average vote was 2.5.

But by late spring, as the bill made its way through the National Assembly and the Senate, tempers cooled and the group began to look at it with pride. While many of the proposals had been watered down, the final legislation was still one of the most comprehensive climate laws France had passed in years. It banned some short-haul domestic flights, ordered a phaseout of advertising for fossil fuels and gasoline, and incentivized electric car and bike purchases. Some of the measures most beloved by the citizens were left on the cutting-room floor. But it was hard to imagine that the law, in its final form, could have existed without the convention’s nine months of work.

When I spoke to Burquier on the phone in May, shortly after the law had passed through the National Assembly, he sounded invigorated, even happy. Although the final law was “very different” from what the convention had hoped for, he said, “Tonight, we can be very proud.”

Roggeman agreed. “I don’t want to see myself as disappointed,” she told me. “I feel lucky — lucky to have had this incredible citizen experience in my life.”

In the two years since they first met, the members of the convention have seen their lives fundamentally changed. Roggeman has spoken about her experiences at a conference at Yale University and recently traveled to the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow. Former members have even formed a new organization, which they call Les Cent-cinquante (“The 150”), and continue to lobby the government to enact their proposals. One citizen, Grégoire Fraty, has written a book about his experience, calling it an “innovative object” that could change democracy forever.

Though he wouldn’t call himself a “militant” about climate change, Burquier’s life has also been transformed. He has met Macron, been on a Zoom call with the mayor of Los Angeles, Eric Garcetti, and learned to be at ease appearing on French TV. Looking back, he describes the convention as a kind of whirlwind: In an interview with FranceInfo, he likened the experience to being in “a washing machine that shakes hard.”

Burquier and other members of The 150 hope climate assemblies spread to other countries, including the U.S. And, he actually believes that they could make it happen. “When Joe Biden was elected, we said, ‘We have to meet the new president of the U.S. and tell him to do a convention,’” he told me. Then he laughed, aware of how self-important the sentence sounded.

“It’s crazy,” he said. “Now we feel we have no limits.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Can ‘the people’ solve climate change? France decided to find out. on Nov 15, 2021.