Landfills bake the planet even more than we realized

Mar 28, 2024

A landfill is a place of perpetual motion, where mountains of garbage rise in days and crews race to contain the influx of ever more trash. Amid the commotion, an invisible gas often escapes unnoticed, warming the planet and harming our health: methane.

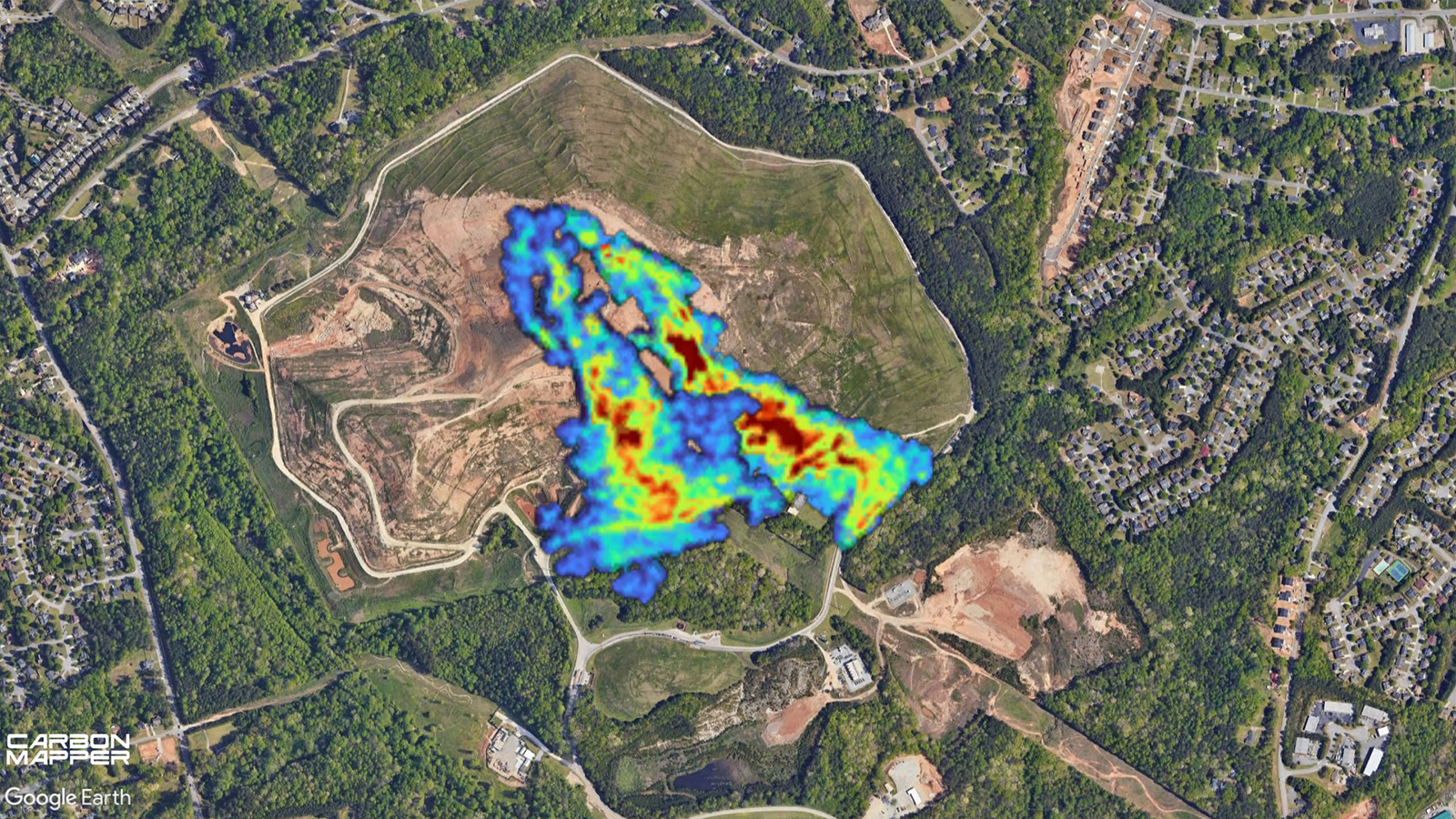

On Thursday, the climate-data sleuths at Carbon Mapper published a study in Science that shows U.S. landfills emit methane at levels at least 40 percent higher than previously reported to the Environmental Protection Agency. At more than half of the hundreds of garbage dumps surveyed — in the largest assessment yet of such emissions — most of the pollution flowed from leaks, creating concentrated plumes. The researchers found these super-emitting points can persist for months or even years, and account for almost 90 percent of all measured methane from the landfills. Tackling these hotspots could be a huge stride toward lowering emission rates, but blindspots in current monitoring protocols mean they often evade detection.

“It’s a very hard problem to get totally right without any leaks at any place,” said Daniel Cusworth, an atmospheric chemist and project scientist for Carbon Mapper, a nonprofit that provides data to inform greenhouse gas reduction efforts. Sometimes Cusworth conducts aerial surveys of landfills and is relieved to find nothing. “And then other times, you know, I’ll see a massive billowing plume that’s three kilometers long.”

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas created by, among other things, decaying trash, and it often seeps through the soil and plastic covers meant to contain it. Although federal regulations require large facilities to use gas capture systems, landfills remain the third biggest source of these emissions in the United States, accounting for over 14 percent of the national total. Because methane is 84 times more powerful than carbon dioxide during its first 20 years in the atmosphere, scientists say reducing the amount of it floating around up there is the quickest way to curb global warming. Doing so also benefits communities: A disproportionate number of U.S. landfills are near marginalized neighborhoods, where gas exposure impacts health or poses an explosion risk.

Leaks that exceed the Clean Air Act’s limit of 500 parts per million are common, as shown by the hotspots Carbon Mapper identified. These areas typically appear after unanticipated events, such as cracks in landfill covers, valve failure in the vast gas collection systems, and other maintenance or construction issues. “They really dominated the total emissions for the landfill,” Cusworth said. The survey found that average release from the most surveyed sites was at least 1.4 times, and sometimes as much as 2.7 times, larger than those reported to the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program.

Georgia

Carbon Mapper

Although federal guidelines require these facilities to track emissions and provide that data to the EPA, current reporting and monitoring methods just aren’t up to snuff, according to the study. Most operators report an estimate, using EPA guidelines, calculated from the amount of trash they take in, not from measured data. Regulators also require facilities to perform walking ground surveys four times a year, but experts like Cusworth say these efforts aren’t frequent or precise enough. Hotspots can easily escape notice because many areas are too dangerous or inaccessible to walk on, and monitoring sensors react only to high concentrations on the ground and wouldn’t catch dispersed plumes. “You can’t manage what you can’t measure,” said Cusworth, adding that it’s a popular cliche in the air monitoring business.

In the survey, the Carbon Mapper researchers flew over landfills with airplanes that captured infrared images, revealing the plumes. Similar remote sensing methods, such as drones and satellites, are among recent technological advances that could keep the pollutant in check, helping facilities find and address leaks quickly. Other innovations to methane capturing systems, such as self-calibrating caps on valves and sensors that can detect leaks, further reduce the risk of failures.

“In the waste sector, specifically, we know what technologies to implement – we’ve known for a number of years. They’re feasible, readily available, and a number of them are actually quite cost effective,” said Kait Siegel, waste sector manager on the methane pollution team at Clean Air Task Force. “We need to have regulations in place.” This upcoming August, the EPA is expected to update its landfill management policies as part of a required 8-year review cycle.

Tom Frankiewicz, a waste sector methane scientist at RMI, which collaborated with Carbon Mapper on the study, said addressing outsized methane sources, like landfills, is urgent due to the short lifespan and extreme potency of the gas, compared to the longer-lasting carbon dioxide. The world won’t see the climate benefits of reducing CO2 emissions for a century, he said. That time frame drops to a decade when curbing methane. “We have to be working on both, and leaning in on methane because it buys us time.” And in the race to mitigate climate change, every moment counts.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Landfills bake the planet even more than we realized on Mar 28, 2024.